More evidence that low-calorie sweeteners are bad for your health

Studies show that artificial sweeteners can raise the risk of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, including stroke.

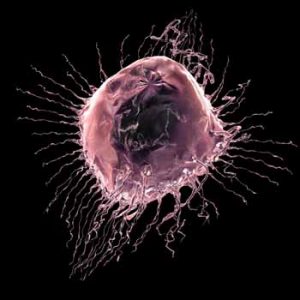

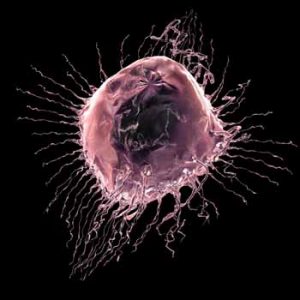

Childhood cancer is on the rise and has been for some time.

Indeed, this trend was one of the first that I ever tackled as a health journalist – more than two decades ago.

It was depressing, then, to see the response to the recent survey by Children with Cancer UK Researchers for the charity analysed government statistics and found that cancer cases in children have surged by 40% in the last 16 years, with 1,300 more cases of children and young people diagnosed annually.

In Britain, more than 4,000 children and young people are diagnosed with cancer yearly and cancer is the leading cause of death in children aged one to 14.

The biggest rise was seen teenagers and young adults aged between 15 and 24 – young people who should be at the beginning of their lives. In this group, the incidence of cancer has risen from around 10 cases in 100,000 to nearly 16. The rise is startling in certain cancers, with colon cancer up 200%, thyroid cancer up by 110%, ovarian cancer up 70% and cervical cancer up 50%.

The analysis suggests that while some of the rise can be accounted for by improvements in cancer diagnoses and more screening, the majority is caused by environmental factors which children can be exposed to in the womb and after birth.

These include: breathing polluted air, smoking, junk food diets, exposure to radiation from x-rays and CT scans but also from mobile phones, magnetic fields from power lines, pesticides and solvents, circadian rhythm disruption through too much bright light at night.

Conventional cancer charities – who make their money by promoting the idea that we are ‘winning the war’ on cancer – scrambled to refute the findings.

In particular, Dr Claire Knight, health information manager at Cancer UK told the Independent newspaper that although environmental factors played a role in causing cancer in adults, “children haven’t had the exposure” adults have, meaning “there just isn’t the time for those factors to do the damage”.

This kind of self-serving ignorance is why I, personally, never give money to Cancer UK.

It is an established scientific fact that children and babies in the womb differ from adults in a number of ways and these can lead to increased vulnerability to environmental insults. For instance:

▪ Many parts of their bodies, for example their brains, bones and reproductive organs, are still developing. During this stage they may be more susceptible to the alterations caused by toxins.

▪ Their systems have a less developed ability to break down toxins.

▪ They eat, drink and breathe more for their weight than adults. This means they take in more toxins per weight than adults. For example, the air intake of a resting infant is twice that of an adult under the same condition.

▪ They crawl around on the floor near dust and other potentially toxic particles.

▪ They are more likely to put things in their mouths and eat things they shouldn’t.

Children’s bodies may also have less capacity to repair damage. In addition, the developing fetus is also extremely sensitive to toxic chemicals. This is because the development of the body is extremely sensitive to complex interactions of signally chemicals (hormones). Disruption of these signals can permanently damage the body’s development and sow the seeds for cancer later in life.

The shock is that these cancers are now showing up sooner rather than later. The fact that childhood cancers account for around 1% of all cancers is of no comfort to a parent whose child is ill. What is more, when we see a dramatic rise in cancers that were once rare it compels us to ask what’s changed.

The answer always comes down to the environment.

If we want to stop living in a world where teenagers are being diagnosed with colorectal, thyroid, cervical and ovarian cancer then things have to change.

Doctors could do more to warn parents about carcinogens in the environment – but they don’t. Researchers could do more to make the environmental case for childhood cancer – but they don’t. Governments could do more to clean up the environment and protect our children – but they don’t.

For these reasons the scientists behind the report should be congratulated for putting the issue out there in the media so that parents can take matters in to their own hands, make different choices about what they eat and buy -and who they vote for – in order to help keep their children safe.

Here’s hoping, because I’d hate to be writing this story again in 20 years’ time.

Pat Thomas, Editor

Please subscribe me to your newsletter mailing list. I have read the

privacy statement