More evidence that low-calorie sweeteners are bad for your health

Studies show that artificial sweeteners can raise the risk of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, including stroke.

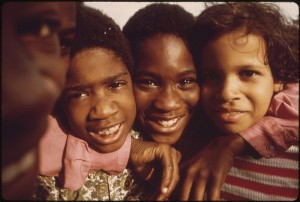

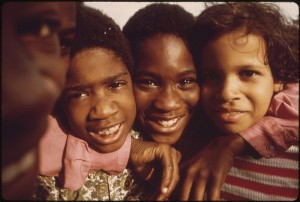

Natural Health News — Where you live could play a larger role in health disparities than originally thought, according to a new study.

The widely accepted belief is that black people are more at risk from certain types of disease simply by virtue of their race.

But when researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health examined a racially integrated, low-income neighbourhood in Baltimore, Maryland, where residents all had a similar levels of income and education, they found that risk has more to do with poverty and lack of access to decent healthcare, than with race.

With the exception of smoking, nationally reported disparities in hypertension, diabetes, obesity among women and use of health services disappeared or narrowed in poorer racially integrated neighbourhood. The results are featured in the October 2011 issue of Health Affairs.

“Most of the current health disparities literature fails to account for the fact that the nation is largely segregated, leaving racial groups exposed to different health risks and with variable access to health services based on where they live,” said Thomas LaVeist, PhD, lead author of the study.

By comparing black and white Americans who are exposed to the same set of socioeconomic, social and environmental conditions, he said scientists were better able to see the true impact of social factors over race.

“When whites are exposed to the health risks of an urban environment their health status is compromised similarly to that of blacks, who more commonly live in such communities,” said Darrell Gaskin, PhD, co-author of the study, deputy director of the Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions.

Effective policy interventions he said need to address “the differing resources of neighbourhoods and improve the underlying conditions of health for all.”

Studies in the UK have come to similar conclusions. In 2008 a report by End Child Poverty, a 130-strong network of children’s charities, church groups, unions and think-tanks, claimed that the gap between rich and poor had become one of the major factors affecting child mortality rates.

Based on a wide-ranging analysis of government data, it noted that children from poor families are at 10 times the risk of sudden infant death as children from better-off homes.

UPDATE October 20, 2011 – A second study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine has found that low-income women with children who moved from high-poverty to lower-poverty neighborhoods experienced important long-term improvements in aspects of their health; namely, reductions in diabetes and extreme obesity.

The study followed 4,498 women and children who lived in impoverished neighbourhoods in five US states – Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and New York – and who enrolled in a programme which gave them access to housing in higher income neighbourhoods.

After 10-15 years of follow-up the researchers found that rates of both morbid obesity and diabetes for the women who had moved to the higher income neighbourhoods than in those who remained in low income neighbourhoods.

As with the Johns Hopkins’ study above, the researchers note that the health problems we sometimes equate with race may have more to do with where people actually live and their access to support and healthcare.

“These findings provide strong evidence that the environments in low-income neighbourhoods can contribute to poor health,” said lead author of the study University of Chicago professor Jens Ludwig

“Given that diabetes and obesity are associated with a large number of health complications and higher cost for medical care, the findings from this study suggest that improving the environments of low-income urban neighbourhoods might improve the duration and quality of life for the residents and lower health care expenditures,” added Robert Whitaker a co-author and professor of Public Health and Pediatrics at Temple University, who is an expert on obesity and diabetes.

Please subscribe me to your newsletter mailing list. I have read the

privacy statement